View Current Newsletter -

Search The Archive

Sign Up - Print

Issue

245

Article

397

Published:

5/1/2018

Chris Burti, Vice President and Senior Legal Counsel

The Court of Appeals in this heavily fact driven opinion clarifies that when a grantor owning one parcel of land with good title, adversely possesses an adjacent parcel and without color of title and then conveys both parcels by deed that only describes the parcel to which the grantor holds good title, the grantees may not tack their possession to the grantor's to satisfy the statutorily required period for adverse possession.

The plaintiffs ("Plaintiffs") appealed from a summary judgment order in favor of the defendants ("Defendants") contending that they were entitled to summary judgment granting them title to real property by adverse possession and that the trial court erred in ordering an easement over their property for Defendants' benefit. The defendants are Bonaparte's Retreat Property Owners' Association, Inc. ("BRPOA"), Bonaparte's Retreat I Property Owner's Association, Inc. ("BRIPOA"), and Charles G. Hamilton, Jr. ("Mr. Hamilton"), collectively ("Defendants").

The Court of Appeals affirmed the trial court in its ruling that adverse position was not sufficiently alleged as a matter of law and reversed holding that a trial court may not impose an easement neither party having raised the issue, the easement was not implied from the evidence, and such relief results in substantial prejudice to the owner of the burdened parcel.

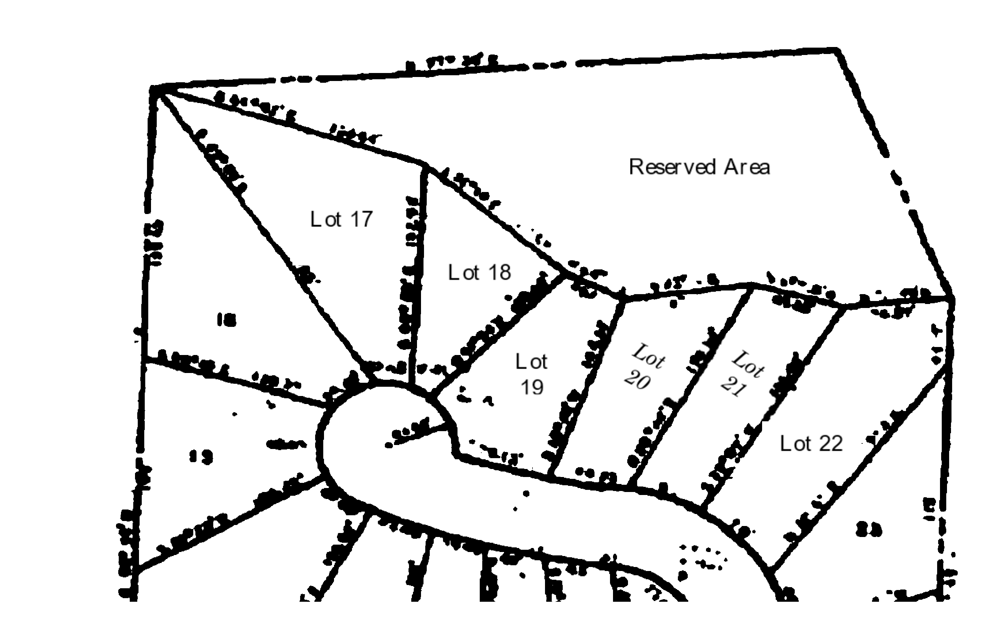

A developer began development of the subdivision at issue in 1972. The developer filed a plat map of the subdivision designating discrete lots for development as well as various "reserved areas." Lot 18 on the plat is shown as provided below, with italicized annotations by the Court of Appeals for legibility:

The reserved area borders the Calabash River. In 1981, the developer conveyed Lot 18 to Gerald Rodney Earney ("Mr. Earney") by warranty deed. The property description in the deed describes only Lot 18 and, by express reference to the plat map filed with the Register of Deeds and does not include any portion of the Reserved Area between Lot 18 and the Calabash River.

BRPOA incorporated in August of 1984 to serve as a homeowner's association for the subdivision. The following year, the developer conveyed several properties to BRPOA by non-warranty deed, including the Reserved Area north of Lot 18. Subsequently, BRPOA failed to file the necessary reports with the North Carolina Secretary of State and was suspended in 1986. In 1991, subdivision homeowners decided to incorporate a second homeowner's association, BRIPOA, rather than revive BRPOA.

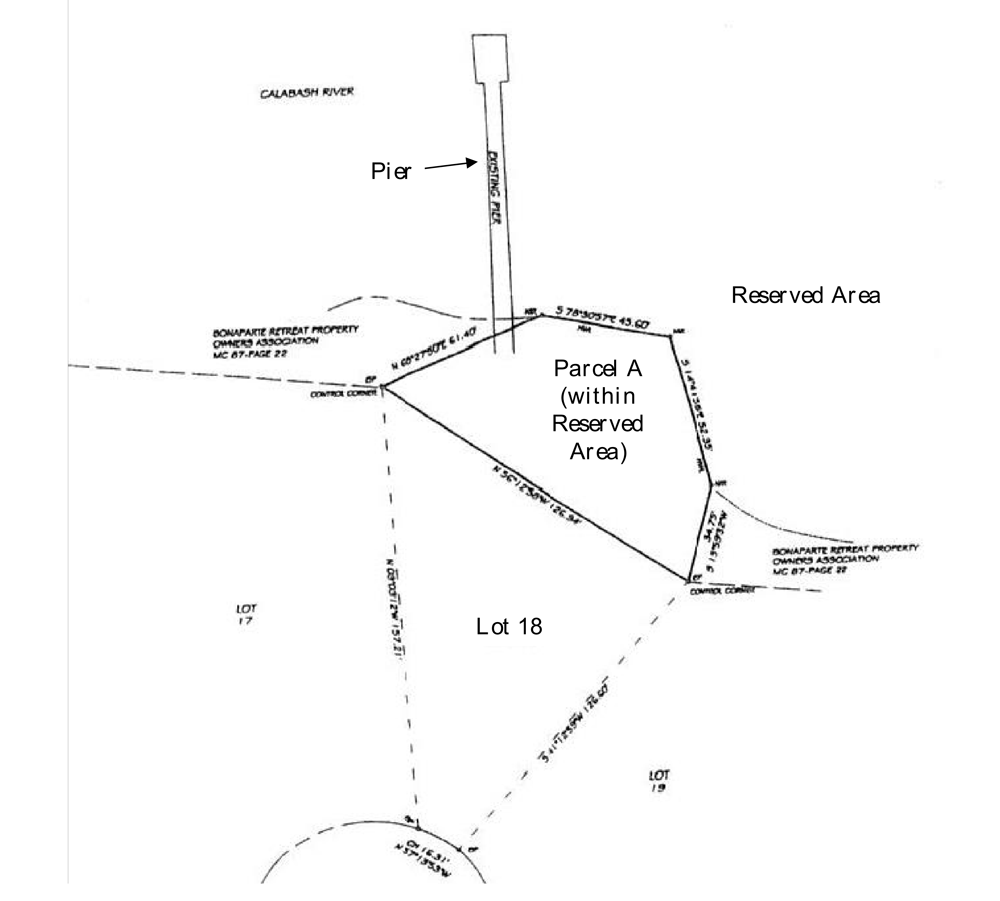

After purchasing Lot 18, Mr. Earney built a Calabash River pier on a portion of the Reserved Area ("Parcel A") as shown on the portion of the survey in evidence (included in the Court of Appeals opinion with italicized annotations by this Court for legibility) as shown below.

In evidence were facts indicating that Mr. Earney mistakenly believed that Parcel A was part of Lot 18, considered Lot 18 to be waterfront property, that he cleared and landscaped Lot 18 and Parcel A, that he docked boats at the pier on Parcel A, used Parcel A to access the pier, and prohibited other people from using the pier without his permission, and that he had a septic tank installed but built no other structures on Lot 18 or Parcel A.

In 2000, Mr. Earney conveyed Lot 18 to Plaintiffs by general warranty deed which recited only Lot 18 by reference to a plat map on file with the Register of Deeds with no mention of Parcel A and the Reserved Area. The opinion recites that although "the real estate listing that led Plaintiffs to purchase Lot 18 advertised the property as waterfront, Plaintiffs never met or spoke with Mr. Earney to inquire about the discrepancy between the listing and all of the conveyance documents, including the deed. Mr. Cole acknowledged that, 'everything [Mr. Earney] signed said Lot 18.'" The remaining factual narrative is taken directly from the opinion:

Plaintiffs, like Mr. Earney, mistakenly believed Lot 18 was a waterfront lot. Beginning in 2001, Plaintiffs started clearing trees and mowed Parcel A. In 2002, Plaintiffs began repairing and renovating the pier, adding a gate and handrails. Plaintiffs tied a rope or chain across the pier entrance, posted no trespassing signs on the pier, and hired a landscaper to mow and maintain Lot 18 and Parcel A during this time. Plans to build a home on Lot 18 coalesced and Plaintiffs hired a contractor to construct their house in 2008. When their contractor surveyed the property prior to the start of construction, Plaintiffs discovered for the first time that they did not, in fact, own Parcel A. Plaintiffs' contractor also told them that construction of their home would require a variance from the Town of Calabash's Board of Adjustment (the "Board of Adjustment"), because Plaintiffs planned to construct the house within 25 feet of Parcel A in violation of the town's setback requirements.

Upon learning they did not own Parcel A, Plaintiffs sought to purchase Parcel A from BRIPOA's board of directors. The sale was stymied, however, because the board of directors discovered it was without requisite authority under BRIPOA's declarations to approve such a transfer.1 Plaintiffs then applied to the Board of Adjustment to obtain the necessary setback variance. In the variance hearing on 24 June 2008, the Calabash Building Inspector/Code Enforcement Officer "acknowledged that [Parcel A] is owned by the Bonaparte Retreat Property Owner's Association (POA) and is used for common open space. The POA property abuts the Calabash River." In ruling on the variance application, the Board of Adjustment made findings of fact, including findings that "the adjacent property to the rear is open space owned by the subdivision's Property Owner's Association[,]" and "the adjoining rear property is required open space for the subdivision[.]" The variance was approved contingent on BRIPOA's consent, and BRIPOA's board of directors provided written consent to the variance to the Board of Adjustment a few days later.

Construction began on Plaintiffs' home in 2013. Plaintiffs placed "no trespassing" signs on Lot 18 and Parcel A to keep people off the building site and used Parcel A to store materials during construction. In October of 2014, Plaintiffs again sought to purchase Parcel A from BRIPOA. When BRIPOA's board of directors once more ascertained that they could not sell Parcel A to Plaintiffs under their by-laws, Plaintiffs rescinded their offer.

1 Nothing in the record indicates that Plaintiffs or BRIPOA's board of directors were aware in 2008 that Parcel A and the Reserved Area had not yet been conveyed from the then-defunct BRPOA to BRIPOA.

Plaintiffs filed a complaint alleging adverse possession against BRPOA and two days later, BRPOA's corporate status was reinstated by the North Carolina Secretary of State. Then BRIPOA's board of directors met and voted to appoint officers for BRPOA, naming defendant Hamilton president of the newly-revived entity. BRPOA then conveyed the Reserved Area including Parcel A to BRIPOA by special warranty deed and Plaintiffs, in response, filed an amended complaint adding Mr. Hamilton and BRIPOA as defendants. In addition to seeking judgment declaring that they owned Parcel A by adverse possession, Plaintiffs asked the court to order the rescission or correction of the special warranty deed. Following a hearing, the trial court granted summary judgment in favor of Defendants, declared BRIPOA to be owner of Parcel A and also declared the existence of "an easement for ingress and egress across. . . Lot 18" in favor of BRIPOA.

The court recognized that N.C.G.S. Section 1-40 permits us to acquire title to real property through adverse possession without color of title if we have "possessed the property under known and visible lines and boundaries adversely to all other persons for 20 years[.]" and then recited the fundamental elements of proving averse possession. The opinion goes on to acknowledge that "a party who has adversely possessed real property for less than 20 years may satisfy the prescriptive period of N.C. Gen. Stat. § 1-40 by 'tacking' his possession to that of a prior adverse possessor." "'Tacking is the legal principle whereby successive adverse users in privity with prior adverse users can tack successive adverse possessions of land so as to aggregate the prescriptive period of twenty years.' Dickinson v. Pake, 284 N.C. 576, 585, 201 S.E.2d 897, 903 (1974) (citing J. Webster, Real Estate Law in North Carolina § 289 (1971)). To establish the necessary privity for tacking, the "'initial adverse possessor [must] transfer[] his possession to a successor adverse possessor by some recognized connection. Thus the privity connection is made out if an adverse possessor transfers his possession to another by deed or will or even by parol transfer.'" "Lancaster v. Maple Street Homeowners Ass'n, Inc. , 156 N.C. App. 429, 438, 577 S.E.2d 365, 372 (2003) (quoting James A. Webster, Jr., Webster's Real Estate Law in North Carolina, § 14-9, at 654 (Patrick K. Hetrick & James B. McLaughlin, Jr. eds., 5th ed. 1999))."

The Court, with appropriate citation, notes that the courts in most other states allow tacking by a grantee of the grantor's adverse possession property beyond the bounds of a parcel description the grantor conveys the parcel described by deed to a grantee who continues adversely possessing the same property. But, again with appropriate citation, the opinion notes that "the North Carolina Supreme Court has repeatedly departed from the majority rule" relying upon a lack of privity, concluding that "Plaintiffs lack the necessary privity to tack their adverse possession of Parcel A to that of Mr. Earney."

Plaintiffs cannot tack their adverse possession of Parcel A to their grantor's adverse possession and they cannot satisfy the twenty year period of adverse possession because, at the earliest, Plaintiffs began adversely possessing Parcel A with their purchase of Lot 18 in 2000. As they brought their action for adverse possession only fifteen years later, their premature action fails as a matter of law.

In the interest of brevity we will not discuss the Court of Appeals' analysis of the plaintiff's ultra vires complaint regarding the POA's actions, however this analysis does reflect the difficulty of prosecuting an ultra vires action in North Carolina after modern amendments to the corporation Acts.

A brief comment on Plaintiffs' final argument on appeal is merited. The Court of Appeals agreed with their argument that the trial court erred in declaring an easement existed across Lot 18 in favor of Defendants so that they by association may access Parcel A. Neither Plaintiffs nor Defendants requested the imposition of such an easement in their pleadings. The trial court did not provide the parties with any notice or an opportunity to be heard regarding such relief before it was ordered. The opinion notes that "Rule 54 of the North Carolina Rules of Civil Procedure permits a trial court to grant the relief to which the party in whose favor [the judgment] is rendered is entitled, even if the party has not demanded such relief in his pleadings." However our Court of Appeals has made it clear that such relief is only proper when it does not substantially prejudice of the opposing party and is improper where a party fails to reference or rely upon any common law or statutory theory giving rise to such relief; the relief is not consistent with the claims pleaded or embraced within the issues presented to the court; or is not suggested or illuminated by the pleadings nor justified by the evidence adduced at trial (citations omitted). Not only did neither party ask for such relief, but the trial court failed to identify the nature of the easement, its location or the legal basis for it. The court's analysis is a good roadmap on how not prove an easement.

The implication for title professionals is that arguing evidence of adverse possession as a basis for establishing title is a measure fraught with peril and subject to uncertain outcomes at best.

- Home

- ALTA Best Practices

- TRID

- Register of Deeds

- Calculator

- Forms

- Priors

- Commercial

- Newsletters

- What Is Title Insurance?

- News

- Your ?'s

- About Us

- Contact Us

- History

- Rates

- Ratings

- Our Creed

- En Español

- Privacy

Resources

Statewide Title, Inc. is a member of ALTA®, the NCLTA and the FEA.